In the days before commercial recordings and electronic media, songs were sung for entertainment around the house, on the job, and in public community settings. A talented singer possessing a repertoire of songs was held in high regard for ability to be “the television of the day.” Ancient British Isles ballads of love and war were sung alongside comic songs, broadsides, songs of historical events, religious/sacred songs and newer creations about local events.

Far

from being the staged event it so often is today, singing in earlier America

was something ordinary people did to pass time, to help the work go more

quickly, to comment on a recent event, to provide a bit of humor, or to

entertain self, family, friends and/or co-workers after the day’s work was

done.

The

style of singing was quite straightforward generally, with little or no

ornamentation and a strong emphasis on the song itself and the story that it

told. The singer took a backseat to the

song.

“Rachel

(a second cousin) was in the kitchen and she was working around and she

was

singing....and she was adding all little grace notes and going up and

going down

and, gee, I thought that sounded good.

So, when I went home a day or two later I’m out in the kitchen doing

the

dishes at the sink, and I’m singing Mom’s ‘Nobleman’s Wedding’ and I

decided

that would sound pretty good with all those little ‘doo dads’ in it, so

I’m

giving it everything I can find to put in it.

About that time Mom comes to the dining room door and she looks out at

me and said ‘Who did you hear singing like that?’...(I told her it was

Rachel)...she said, well, maybe her songs sound alright like that but

mine

don’t, and if you’re gonna sing my songs you sing them the way they

belong

or you shut your mouth. Needless to say, I shut my mouth.”

-- Sara Cleveland, Ballad Singer, Brant Lake

Not

everyone sang, certainly, and only some were thought of as “good singers,” but

that label often had more to do with the quantity and quality of songs the

singer knew, and less to do with vocal quality.

Accolades for older singers so often contain some variation of the

phrase “boy, I’ll tell you, he could sing all night and never sing the same

song twice.”

Not

everyone sang, certainly, and only some were thought of as “good singers,” but

that label often had more to do with the quantity and quality of songs the

singer knew, and less to do with vocal quality.

Accolades for older singers so often contain some variation of the

phrase “boy, I’ll tell you, he could sing all night and never sing the same

song twice.”

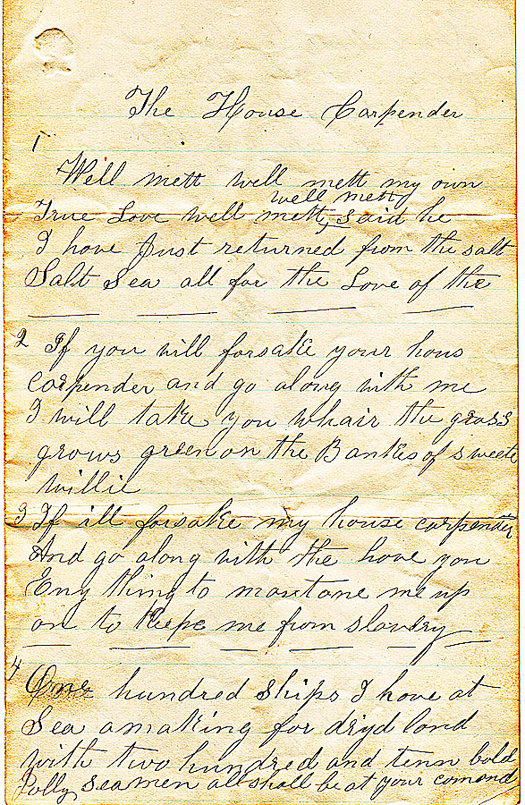

The general repertoire of oral tradition songs in the Adirondacks numbered in the thousands, with some pieces found more frequently than others. It was not uncommon for traditional singers to have 100 or more full songs in their memories at any given time, with a few singers (that we know about) possessing repertoires of over 200 songs.

Typically, no two singers outside of an immediate family--and sometimes within one--would have identical versions of the same song (there being exceptions, of course). Because of the nature of the oral tradition, the changes one makes to a given song during and after the time it is committed to memory, conscious or not, result in infinite variations on both lyrics (text) and melody (tune).

Barrooms,

lumber camp bunkhouses, front porches, parlors, work bees (quilting, husking,

barn raising, etc), fireplaces, kitchens and general stores would each provide

an atmosphere and context ripe for the singing and sharing of these tales set to music.

Lumbercamp Singing

By

the mid nineteenth century, New York State had surpassed Maine as the

preeminent lumbering state in

America. With the main logging season

occurring in the fall, winter and early spring months, lumbermen and camp cooks

would trek miles into the woods in October or so, often not to see the outside

world again until April, or later.

Working six days a week for twelve to fourteen hours a day in the wintry

woods left precious little time or energy for recreation, although to say that

entertainment was prized in these off hours would be an understatement. We have many

accounts of lumber camp employment bolstered by one’s ability either to

sing a song, tell a story, fiddle a tune or dance a dance.

By

the mid nineteenth century, New York State had surpassed Maine as the

preeminent lumbering state in

America. With the main logging season

occurring in the fall, winter and early spring months, lumbermen and camp cooks

would trek miles into the woods in October or so, often not to see the outside

world again until April, or later.

Working six days a week for twelve to fourteen hours a day in the wintry

woods left precious little time or energy for recreation, although to say that

entertainment was prized in these off hours would be an understatement. We have many

accounts of lumber camp employment bolstered by one’s ability either to

sing a song, tell a story, fiddle a tune or dance a dance.

“An

interesting story is told

concerning (Theodorus Older’s) arrival in Keene Valley, where he

settled about 1870. At dusk of a winter day a powerfully built

stranger stopped into Crawford’s Store

and, without saying a word to anyone, walked

to the stove and began to warm himself.

After a few minutes, with his back

to the stove, he began softly singing to himself. In short order more

people were entering than leaving the store and

those who had business to transact did so

in lowered voices. The tall stranger

remained singing until 10 or 11 o’clock at night

when he finally spoke to ask: ‘Any work

around here? I’m a chopper.’ A job

was quickly found for him in the area.”

-- Peter McElligott,

referring to singer/fiddler Lawrence Older’s grandfather

Occasionally

on weekday evenings, and most often on Saturday nights (with Sunday being

the traditional day off), singing

lumbermen in camp would take their turn on the “deacon seat” in the bunkhouse,

offering songs old and new in an unaccompanied (“a capella”) declamatory style

for the entertainment of themselves and their co-workers. The songs in a typical Adirondack lumberman’s

repertoire contained a mix of logging and non-woods themes, and with the

variety of men one worked with from camp to camp and year to year, there were

endless opportunities to pick up new songs.

Some

of the more commonly found songs in the Adirondack lumbercamp repertoire, circa

1880-1930, are: “The Wild Colonial Boy,”

“The Wild Mustard River” (aka “Johnny Stiles”), “The Ballad of Blue Mountain

Lake,” “The Farmer’s Curst Wife,” “The Darby Ram,” “Barbara Allen,” “The Days

of ‘49,” “The Little Mohea,” “The Flying Cloud,” “Johnny Sands,” “The Lass of Glenshee,” “The St

Albans Murder,” “The Cumberland and the Merrimac,” “Once More A-Lumbering Go,”

“The Shanty Boy,” “The Farmer Boy,” “James Bird,” “The Woodsman’s Alphabet,”

“The Flat River Girl” (aka “Jack Haggerty”), “The Backwoodsman” (aka “One

Monday Morning,” “The Dance at Clintonville”), “Joe Bowers,” “Lord Lovell,”

“Kate and Her Horns,” “John Riley,” “The Banks of the Sweet Dundee,” “Lord Randall,”

“Cole Younger,” “A Shantyman’s Life”, and perhaps the most ubiquitous of all…“The Jam on

Gerry’s Rock .”

“I probably sung that thing maybe 5,000 times…That was the big one for a majority of the fellas. ‘Course, it was a lumberjack song, you might say...”

-- Ted

Ashlaw, referring to “The Jam on Gerry’s Rock”

-- Lawrence Older, referring to “The Jam on Gerry’s Rock”

“Those deaths occurred in so many

areas…in fact, I’ve heard that name changed to

an area death...because it matched so

perfectly the happening that they knew of,

they used a different

name. When I married my first

husband…his mother sent me all the words, and they were a little bit

different (from the version sung by my grandmother).”

-- Ermina Pincombe, referring to “The Jam on Gerry’s Rock”

The importance of lumber camp singing and song repertoire cannot be overemphasized in any look at Traditional Adirondack Music. Singing lumbermen highlighted on this website include “Yankee John” Galusha, Ted Ashlaw, Eddie Ashlaw, Steve Wadsworth and Lawrence Older, although we see the influence of the woodsman’s repertoire for numerous other Adirondack singers.

Barroom Singing

Often an extension of lumber camp singing, barroom or tavern performance was an art form all its own in Adirondack towns and outposts of old. The barroom, if we are to believe old stories told by woodsmen and others, was the first place many loggers would steer in the springtime, or on weekends, once they had a little change in their pockets. A singer with a decent repertoire of songs, once discovered and called upon, would sing song after song to the delight of the other patrons, and would be treated with special status for the remainder of their stay at the tavern.

“Draft beer was ten cents. You could go in there with one little dime in the afternoon, and you’d come out that night walking sideways.”

-- Dick

Law, Traditional Singer, Hermon

On

a lucky night, one might encounter several singers of the old-time songs

congregated at a woodsmen’s tavern.

“… Tupper Lake was always pretty

good for singing. You’d get in there, and the group

would be singin'-- five or six of us, sometimes more. (At the Grand Union Hotel) there was a big bunch would come that were all

good singers. We’d get in a huddle at the end of the bar, and we’d whoop her up there.

Tupper Lake is shot now...you

start singing in a bar and they turn the

jukebox on.”

-- Eddie Ashlaw, Traditional Singer, Parishville Center

The

tavern setting, like the lumbercamps, also gave singers the opportunity to

“pick up new pieces,” to hear major change versions and minor change variants

in texts and tunes of their own songs , and to experience other styles of

singing in a relaxed, informal setting.

Home Singing

Some

of our most important and well-known Adirondack singers, including Sara

Cleveland and Lawrence Older, mention hearing and learning their first songs at

home from members of their family. In

the home setting, singing ranged from a solitary activity while washing dishes

or tending gardens to a group activity with family members gathered around on a

winter’s night. If the “family around

the hearth” image sounds a bit romantic, this is how Sara Cleveland described

it:

-- Sara

Cleveland, Ballad Singer, Brant Lake

Singing

around the house was a natural part of life in many homes, and Adirondack

singers and musicians have often mentioned that “you didn’t think anything of

it at the time.” The songs would become

part of the rhythm of home life, and without much effort at all, some of them

would end up in the next generation’s repertoire. Other more lengthy songs would be carefully gone over time and

time again until the new singer had “gotten it all together." Songs learned from

family members in this way tended to stick with the singers, and would bring

back special feelings when sung.

Community

Singing

Outside of the tavern/barroom setting mentioned above, there were several other important public places within Adirondack communities where singing would take place. These include work bees, family gatherings, Grange meetings, talent shows, local school events, minstrel shows and more.

“You’d take around Christmas time. Why, you don’t see it no more, but we’d be three weeks (visiting) from one house to the other. Team on a set of sleighs. And probably fifteen or twenty people on it. We’d go from one relative to the other...and you’d always find about ten up singing all the time, ten drunk. There was once in awhile a fiddler, but that’s about all. Singing in French and English. And… there was a lot of songs...and they’d go to the week after New Years. They called that ‘little NewYears’...Well, that’s the way they spent Christmas years ago.”

-- Eddie Ashlaw, Traditional Singer, Parishville Center