- The Dance

- Learning to Play

- Styles & Repertoire

- Lumbercamp Fiddling

- A 1920's Resurgence

- 1940's - Present: Big Changes

As came the earliest settlers to the Adirondack Mountains, so came their portable musical instruments. Jew’s harps and fifes were among the first, followed by button accordions, mouth harps (harmonica) and later 5-string and tenor banjos, mandolins and guitars, stationary instruments like the pump organ and the piano, and always the smaller “homemade” instruments such as the bones and the spoons--but no folk instrument ever enjoyed as much popularity in this area as the folk violin, also known as the fiddle.

“Music is food for the soul, and

what better music is there than a good fiddle tune?”

Fiddling

in the Adirondack woods was widespread, and the fiddler enjoyed a special

position of status in the community. The

sweet sounds of the old jigs, reels, polkas, schottisches, waltzes and

hornpipes accompanied family life at home, entertained visiting neighbors and

friends, lifted spirits in isolated wintry lumbercamps and, perhaps most importantly, provided the music

for community dancing. In fact, it is

impossible to separate fiddling and instrumental music-making in the

Adirondacks from these dances.

In

the summer of 1902, the Canton Commercial

Advertiser published the following

poem by Earl Leo Brownson:

The Country Dance |

|

| Did you ever go to a country dance, A real old kitchen hop, Where when they’d get to dancing they Don’t ever want to stop? Well, if you never did you ought To go and see the fun, That don’t let up one minute till The rising of the sun. I’ve been to one or two myself, And like to see them dance. The old folks and the young ones that Like wild colts kick and prance. It’s Money Musk, the Tempest, and The old Virginnia Reel, And Fisher’s Hornpipe loud and fast, That puts springs in your heel. The Devil’s Dream, Varsouvian; And Durang’s Hornpipe old Hull’s Victory, and Speed the Plow That makes the timid bold. Upon the table near the wall The fiddler is placed; He’s old and bent and gray and bald And swarthy wrinkled faced. He swings his fiddle into place, All dancers take the floor-- “Salute yer partners all,” he cries, “And right and left first four-- Grand ladies’ change, and back to place-- Swing partner once around-- All promenade around the hall-- Four couple Shav’er down.” |

The fiddler screeches out the time Without a skip or break: -- “Swing partner once and a half around, And then your opposite take-- All form in line and walk around--” Just hear the fiddler play, “And shassay out and back again-- Then all hands run away-- Grand right and left, and swing your own-- And prominade to seat:--” His fiddle drops upon his knee And the figure is complete. Old farmer Green and widow Black; By special invitation, Get on the floor and dance a jig Till both are near prostration. Then someone says, “It’s time to eat,” And all crowd to the table To get a seat if possible, And eat as long as able: Cold meat and biscuit, coffee too, And quantities of cake-- All things to make you hungry and You heartily partake; And then you dance till broad daylight, A score or more selections. And go home in the early morn With happy recollections. |

The Dance

By

all accounts, day-to-day life in the Adirondack wilderness was a struggle,

leaving precious little time for recreation or social gatherings. When people did come together, they liked

nothing better than to chat a while, share some food and/or drink, and dance

the night away.

“I used to play about twice a

week...kitchen hops...Then, everybody was poor and they’d have it right in their own home, invite their friends...Boy,

I’m gonna tell you, they were ambitious

too, they wanted a lot of them (dances)...(Fiddlers) would play from nine until two in the morning, square dance after

square dance.”

-- Emmett

Hurley, Fiddler, Hannawa Falls

Taverns,

meeting halls, Granges and other public buildings would jump to life on a

Saturday night, and it was just as common for these jovial affairs to be held

right in someone’s home. With the furniture

cleared from the main room(s) of the house, the musician(s) would be placed in

a corner (or even on top of the wood stove when space was really tight!) and the

dance would begin. Neighbors would come

from miles around to partake in the music, the dancing and the socializing so

important to life in these rural communities.

Taverns,

meeting halls, Granges and other public buildings would jump to life on a

Saturday night, and it was just as common for these jovial affairs to be held

right in someone’s home. With the furniture

cleared from the main room(s) of the house, the musician(s) would be placed in

a corner (or even on top of the wood stove when space was really tight!) and the

dance would begin. Neighbors would come

from miles around to partake in the music, the dancing and the socializing so

important to life in these rural communities.

In earlier days, the dances often revolved around work that needed to be done. An 1833 visitor to the Lake George area attended both a raising bee (for a public-house) and a quilting bee on the same visit; each was followed by dancing to the music of a fiddler. Corn huskings, apple parings, barn raisings and other work “bees” requiring many hands would similarly end with a night of longways, square and/or round dances.

More

commonly as time went on, the dance became an event in and of itself--something that was planned in advance and anticipated with excitement

throughout the week. Four, five, six, eight hours long--it wasn’t unusual for

the next day to be dawning before the last weary dancers were turning back

towards home.

“I’d get home (from work) and wash up,

change, shave, and eat my supper, get in my

car and go to (play) a dance..They would dance until three o’clock, three in the morning, then I’d come home, get

a few winks of sleep and go to work. I couldn’t afford not to work and I

couldn’t afford not to take up the dancing...So, that’s the way that was.”

-- John Russell, Fiddler, Parishville

Often

you’d find just a single musician providing the music--and the calls!--for

dancing. One musician was all that was needed, and indeed all they had. Jew's harp, harmonica, accordion or pump organ--each would be employed on occasion. But the dancers almost unanimously preferred the clear, happy strains of the fiddler.

From the Adirondack Record-Elizabethtown Post,Thursday, October 9, 1924, article titled “Lewis Grange Members Dance to Music Furnished by Man Almost 92 Years Old":

“The violin responded to the deft touch of the venerable John Hathaway, ‘Uncle John’ as he is locally known, everything from the Fisher’s Hornpipe down being played. He will be 92 years old if he lives till Dec. 18th next, having been born in Lewis Dec 18, 1832.”

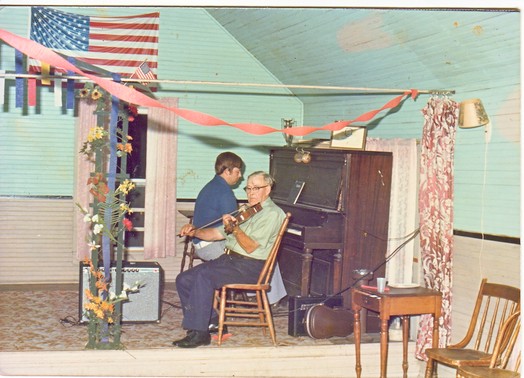

When

more than one musician was available, a common arrangement was to have a piano

or pump organ playing “backup” to the “lead” of the fiddle. The style of accompaniment is known as

“chording,” with the backup musician providing harmony (chords) and rhythm in support of the melodic

playing of the fiddler.

Another common format was two fiddles. In this case, the additional fiddler would either “second” the melody by playing in unison, or play a suggestion of the chords behind the melody of the lead fiddler. Larger groups with banjo, accordion, even mandolin and/or guitar weren’t uncommon as time went on.

The earliest dances were the longways or contra dances (aka “string dances”) brought to the area by settlers from New England and elsewhere. Lively Old- (and New-) World jigs, hornpipes and reels were the order of the day, with many of the dances sharing the name of the tune that propelled them (“Money Musk,” “Portland Fancy,” “Opera Reel,” etc).

Next

came the square dances, or “quadrilles,” originally from France, and the round

dances such as the waltz, polka and schottische. These would remain popular right up through

the 20th century, sometimes coexisting with the old longways dances

favored in some communities, or often supplanting them entirely.

Next

came the square dances, or “quadrilles,” originally from France, and the round

dances such as the waltz, polka and schottische. These would remain popular right up through

the 20th century, sometimes coexisting with the old longways dances

favored in some communities, or often supplanting them entirely.

Although country dancing in New York State--and elsewhere in America--has endured at least a few cycles of popularity and decline from the late eighteenth century to the present, Adirondackers seem to have been somewhat buffered from these trends for most of that time. It wasn’t until roughly the World War II era, with modernization bringing exciting new entertainment options, that the dances began to steadily fall off in popularity. Old ways were being left behind, and the community dance was one of the casualties.

Older

Adirondack residents of today, and back to at least the early 1970s when Robert

Bethke conducted his field research in St Lawrence County, lament the loss of

these dances and the feelings of community, family and good times they

engendered. Square, round and contra

dancing can still be found and enjoyed in the twenty-first century Adirondacks, but it

has become largely separated from the rhythms of work and community life.

“My grandfather and my Grandma Craig

used to play for dances in the Red Man’s

Hall upstairs over the printing office in Wells. Now the building is gone and everybody that did it is gone.”

--Ermina Pincombe, Singer and Musician, Benson

Inspirations and Early Learning

Most Adirondack fiddlers and musicians grew up hearing fiddle music in their own homes. Many traditional Adirondack musicians have childhood memories of falling asleep to the sounds of the fiddle and other music being played by family members, relatives and neighbors.

In

musical families, the old tunes were a constant backdrop, a basic part of

life. To hear Vic Kibler or Ermina

Pincombe tell it, you couldn’t help but pick up an instrument at some point

(often a “forbidden” one of Dad’s hanging on the wall) and try to find the

notes for yourself.

“I think music is

genetic. I think it's passed from

generation to generation and it's just

like any type of [activity]. Some people

have art and are artists. They can paint, and it's just in their blood to be able

to paint, and some people have music in

their blood and it's a natural thing.

And you see it with families....Music was always in my family.

I've seen families that were mechanically inclined. They could

tear an engine apart, put it back together, yet they might not be able to do music or art.

Everyone has their own talents.

“I think music is

genetic. I think it's passed from

generation to generation and it's just

like any type of [activity]. Some people

have art and are artists. They can paint, and it's just in their blood to be able

to paint, and some people have music in

their blood and it's a natural thing.

And you see it with families....Music was always in my family.

I've seen families that were mechanically inclined. They could

tear an engine apart, put it back together, yet they might not be able to do music or art.

Everyone has their own talents.-- Don Woodcock, Fiddler, Kendrew Corners

Adirondack fiddlers learned and played their music largely “by ear,” just like the generation before, and were more comfortable playing this way than “by note” (reading printed music) on the whole. Much of their technique and repertoire was learned from family members and others in the community, but not always through formal “teaching,” so often it came from listening and watching, and experimenting.

“All

of us that taught ourselves to play, we didn’t know what to do with the bow and we just made sounds, and that’s the

way the tune came out.”

-- Lawrence Older, Fiddler, Middle Grove

The Adirondack fiddler played a repertoire of “old-time” tunes that went hand-in-hand with community dancing, and he or she learned the most important lessons of the dance musician as a child simply by attending dances, and again at home from family members who played.

“My grandma would take me on her knee when I

was tiny, and she’d say, ‘Listen to

me: this is the time that goes with that tune, not just exactly the way your

Dad plays it.’ And she’d trot her foot, and me on her knee,

so I got that rhythm, and she’d hang on

both my hands, and she’d dum-de-dum-de-dum-de-dum like this, until it was drilled into my head.”

-- Ermina Pincombe, Singer and Musician, Benson

With

such a rich fiddling tradition in the area, even those players without music in

the immediate family had no trouble finding outside sources of inspiration and

repertoire. You could always find a

fiddler at the dances.

“My mother used to take me to dances

when I was young, just to hear the music, because

I could pick up a piece of music awful easy, and it didn’t take long for me to get to playing that same music that I

was hearing...if it comes to me the next morning,

I could play it.”

-- John Russell, Fiddler, Parishville

Visits

to other musicians’ homes or communities were common as well. Adirondack fiddlers were known to walk miles

to sit and listen to a fiddler with a repertoire or style different from their

own.

As a fiddler got a handful of tunes under their belt, dances would provide the perfect setting to hone their skills. Often, Adirondack fiddlers report playing their first dances while in their early teens, with some as young as ten years old.

Fiddling Styles

To

be sure, every Adirondack fiddler had his or her own style of playing and

unique set of influences. French

Canadian fiddlers were said to play “notier” and sometimes in difficult keys

like F and Bb, whereas numerous local fiddlers played more plainly and favored

the open-string keys of G and D. Lewis

“Lukie” Nichols of Speculator played

longbow style, generating several notes from each bowstroke; more commonly,

area fiddlers would use the old “sawing it off” method of one bowstroke per

note.

"There was every style in the world

that you can think of. There wasn’t just

this one ‘hacksaw’ type of playing,

where they dahh-da-da-dahh-da-da-dahh

(imitates bowing of a fast reel), you

see, they didn’t have that time to them at all.

Every tune you’d hear, the

fiddler would have his own way of doing it, and of course the tunes were kind of a personal thing to

them. I think the style maybe was more important to people somewhere else, but here

it wasn’t the style, it was the tunes.”

-- Lawrence Older, Fiddler, Middle Grove

One

strong fiddler could influence the playing of an entire community. Others had no role models in local proximity,

instead taking what they could get from printed sources and from any and all fiddlers they chanced to encounter

(and later from radio and other mass media).

Some held the fiddle down in the crook of the arm, whereas many others held it under the chin.

One

strong fiddler could influence the playing of an entire community. Others had no role models in local proximity,

instead taking what they could get from printed sources and from any and all fiddlers they chanced to encounter

(and later from radio and other mass media).

Some held the fiddle down in the crook of the arm, whereas many others held it under the chin.

On

the whole, though, the predominant style of fiddling in the region was to take

a “clean,” straightforward approach to the tunes with little or no

syncopation. The melody was rendered as

accurately as possible, and was generally played “bare” with minimal

ornamentation (trills, flourishes, slides, double stops or harmony ) and

without extra notes connecting one phrase to the next. Exceptions occurred,

however, for playing certain old Scottish tunes also rendered on pipes, as well

as some tunes from the Irish and French Canadian heritages.

Fiddling Tunes and Repertoire

What tunes did they play? “Money Musk,” “Fisher’s Hornpipe,” “Opera Reel,” “Rickett’s Hornpipe,” “Soldier’s Joy,” “Portland Fancy,” “Devil’s Dream,” “Durang’s Hornpipe” were very po9pular. These, and other, dance tunes mostly of British and Irish origin were learned both from oral tradition and from printed sources such as tune books and personal manuscript books. Certainly there were plenty of jigs, reels and hornpipes in the early Adirondack fiddler’s repertoire along with some “airs” or song tunes, and perhaps an original composition or two.

“In

the year 1758 Sir William Johnson brought 600 Scottish families to the Johnstown area, and they left their weight in

music. All their descendents are playing an awful lot of Scottish music, and they don’t even know they’re Scottish anymore.”

-- Lawrence Older, Fiddler, Middle Grove

As men would cross the border between New York and Canada seeking seasonal employment, new tunes were shared and taken back home, enriching the local repertoire. This interchange took place in both directions, and has been continuous since early European settlement in the Adirondacks.

As time went on and newer round and square dances were introduced, fiddlers accordingly began playing more waltzes, schottisches, quadrilles, polkas and popular songs of the day. Sheet music, traveling shows and later radio, recordings and television would all offer fresh supplies of melodies.

Many Adirondack fiddlers played at least a few tunes for which they had no known name. These were generally family tunes that had been passed down through the generations and whose origins had been lost to time. When a title was needed, they often ended up with names like “Uncle Maurice’s Tune” (Vic Kibler), or “Streeter’s Reel” (Don Woodcock), named for the person with whom the piece was associated.

Other

times, a well-known tune might have a local name, or even five or six different

names in different communities. One

example would be the French Canadian dance tune “Glise aSherbrooke,” which Roch Chaloux

called “Home Sweet Home”and Cecil Butler called “Irishtown

Breakdown.”

“(Song titles) don’t mean

anything much because I collected one (a

fiddle tune) up there (in Canada)

once called ‘The Ontario Reel’ that we danced around here all our growing up years. (We called it) ‘Benson’s Favorite’ because

Benson was the only one that

ever played it.”

-- Lawrence Older, Fiddler, Middle Grove

Some tunes just plain had no titles! When the square dances were first becoming popular, collections of newly composed quadrilles came along with song titles like “Quadrille in F and C” or “Quadrille #1.”

Adirondack

fiddlers also had a few tunes they’d composed themselves, sometimes quite

unintentionally.

(See the Fiddlers

& Dance Tunes section for more on the local and original fiddle tunes of

the Adirondacks.)

Fiddlers in the

Lumber Camps

The

portability of the fiddle made it the perfect instrument to bring into the

woods during the lumbering season, and we have reports of men doing just

that. The lumber camp setting, with

dozens of men living together in tight quarters for weeks and months at a time,

provided a great atmosphere for the sharing and enjoyment of the old-time

tunes. If there was a man in camp with a

fiddle, he could count on being pressed into service, and sooner rather than

later.

Right

from the start, the lumber camps were also an important setting in which the

Adirondack fiddler would hear and learn from the playing of musicians from

other countries and cultures. Anglo

Canadians, French Canadians and Scotch-Irish were among the first, with

arguably a stronger fiddling tradition than what existed already in the

region.

“I think it’s all French and

Scottish influence, really French Canadian influence from the loggers

that came here.

They came with harmonicas and fiddles wrapped

up in burlap bags and all kinds of things and they brought their music

with them. That was the first contact (for Adirondackers) with the

fiddle music, usually.

They didn’t know how to play, they didn’t have pianos in their homes.”

-- Ermina Pincombe, Singer and Musician, Benson

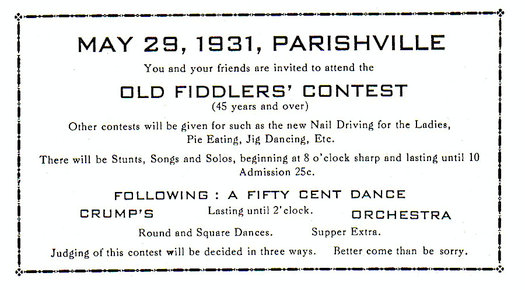

Fiddlers Conventions & Contests

Look

through a handful of editions of any Adirondack community newspaper from the

late 1920s and you’re sure to find advertisements, feature articles and reviews

on fiddling programs, gatherings and contests held around the region. Often staged at public schoolhouses and other

public venues, these events would tend to bring out older fiddlers born in the

1850s and even earlier to play the old-time jigs, reels and hornpipes to the

delight of packed houses.

"Old Time Fiddlers Becoming Popular," The Record-Post, Thursday, February 11, 1926:

“One 1926 old-time fiddlers’ contest at Black Brook, (AuSable Valley) saw area fiddlers Bob Blackbird, Pat Doyle, Ben Wright, Arthur Yelle, Louis Belrose, Joe Carmel and M. Senecal competing for the prize. In that same year, at The Palace in Lake Placid, Upper Jay fiddler Mr. Robinson (perhaps Orville M. Robinson, a nineteenth-century fiddle maker from Upper Jay) took first place, nudging out AuSable Forks’ Senecal, who came in second, and a Mr.Trombley of Peru, who took third. Each of the fiddlers at this contest played to the piano accompaniment of Mrs. Orsia Vassar.”

The contests and meetings helped in no small part to bring a few old fiddles (and fiddlers!) out of the closet and back into circulation. The events also served to keep the old tunes alive and inspire new generations to take up the old dance music.

More Changes

Things

would change again for fiddling starting in the 1940s. As radio, television and other entertainment

became more widely available in the mountains, the dances and contests started

to lose some measure of popularity. The

fiddler felt this loss in the form of fewer opportunities to play the

music. As a result, old-time fiddlers

increasingly began to seek each other out, getting together socially to play

the old dance tunes for their own enjoyment.

Spouses and others would tag along to visit with each other and relive

happy times through the music.

Radio, commercial recordings and (later) television affected the fiddler in another profound way. Each medium brought new fiddle sounds and styles from distant places right to the Adirondack musician’s doorstep. Cowboy, “Hillbilly” and Country and Western sounds all became very popular in the North Country, as did the music of Canadian fiddlers like Ward Allen, Bill Guest, Andy DeJarlis, Rudy Meeks and others, along with everyone’s favorite, Don Messer, Canadian old-time fiddler. Messer was born near Fredericton, New Brunswick in 1909 and learned his music early from neighbors, family and at local dances just as so many Adirondack musicians did. He also had some formal instruction in Boston over a three-year period. By the age of twenty, he had started a radio career that would last for the next forty years, first out of St John, New Brunswick, and later from Prince Edward Island. Broadcast widely and often over CBC radio, Messer and his group (Don Messer and His Islanders) were hugely influential on fiddlers from both sides of the border throughout the 1940s to early 1970s.

New York fiddlers simply could not get enough of Don Messer’s playing. They loved his tunes, which were from the same Scottish, Irish and French Canadian roots as their own, and they especially loved his smooth clean fiddling style, which became known as the ”Down East” style. As commercial country music moved towards amplified instruments and newer sounds, Don Messer was the source for old-time music in this new age of “dialed in” entertainment. In fact, many informal gatherings of fiddlers would center around a Messer radio or television show, with the assembled fiddlers alternately playing and listening to/commenting on the tunes Messer and band were playing.

Don Messer’s influence on Adirondack fiddlers of the 1930s and beyond cannot be overemphasized. The Messer style of playing became synonymous with old-time fiddling in the northeastern U.S. and in eastern Canada. Many of the tunes he popularized (“Chinese Breakdown,” “Little Burnt Potato,” “Don Messer’s Breakdown,” and “Big John McNeill,” to name a few) became standard pieces in the Adirondack fiddler’s repertoire, and the fiddling contests increasingly adopted the “Down East” style as their benchmark in evaluating fiddlers.

Fiddling Today

Today,

there are many fiddlers living and playing inside of the

Adirondack Park—beyond the boundary line, too!-and thanks to the efforts of

Alice Clemens and the New York State Old Tyme Fiddlers Association, an active

chapter known as the Adirondack Fiddlers Club continues to meet and

perform.

Fiddling represents one of the most continuous

traditions of the region, with active players who can trace fiddle playing back

several generations in their own families. The tunes and influences have changed to run the gamut of musical

styles, and some Adirondack fiddlers may prefer Southern breakdowns to French

Canadian or Adirondack tunes. But still,

the fiddle music carries on each time it is played, shared, danced to and

otherwise enjoyed.

“(Fiddle music) has been here in

this country for as long as the country has been here,

and I think it’ll always be here.”

-- Clarence “Daddy Dick” Richards, Musician, Corinth